Creative Precision

For Le Bonheur Plastic Surgeon and Co-Director of the Craniofacial and Cleft Program Robin Evans, MD, FACS, FRCSC, virtual planning for a craniofacial surgery is a beautiful marriage of art and science, form and function. And it’s providing innovative, unique solutions for some of the most complicated pediatric craniofacial surgeries in the country.

Virtual surgery planning in Le Bonheur’s Craniofacial and Cleft Program uses the latest in 3D technology to build a careful, unique plan for surgery for each child. This revolutionary approach to craniofacial surgery is leading to better outcomes for kids and accurate, specific measurements of surgery results in a field that has previously lacked this precision.

“Virtual planning allows me to try unique options before getting into the operating room making sure it’s the right operation for the right patient,” said Evans. “We’re very proud of the fact that we don’t treat everyone like a cookie cutter. We try to bring uniqueness into whatever we do.”

Thanks to this technique that provides a quantified approach and careful planning, Evans and his team are building a reputation for successfully taking on the hardest cases and reconstructions. Virtual planning for craniofacial surgery allows Evans to accurately plan and measure postoperative changes in bone structures and soft tissue with innovative techniques that use the latest technology available. This allows him to know before the operation starts what results will look like for each child.

“Much of what we do as plastic surgeons involves both form and function, and those things overlap,” said Evans. “With new technology we can analyze things like skull volumes and symmetry. It’s the beginning of a paradigm shift in the way we think about surgical outcomes.”

Reshaping Lives Through 3D Printing

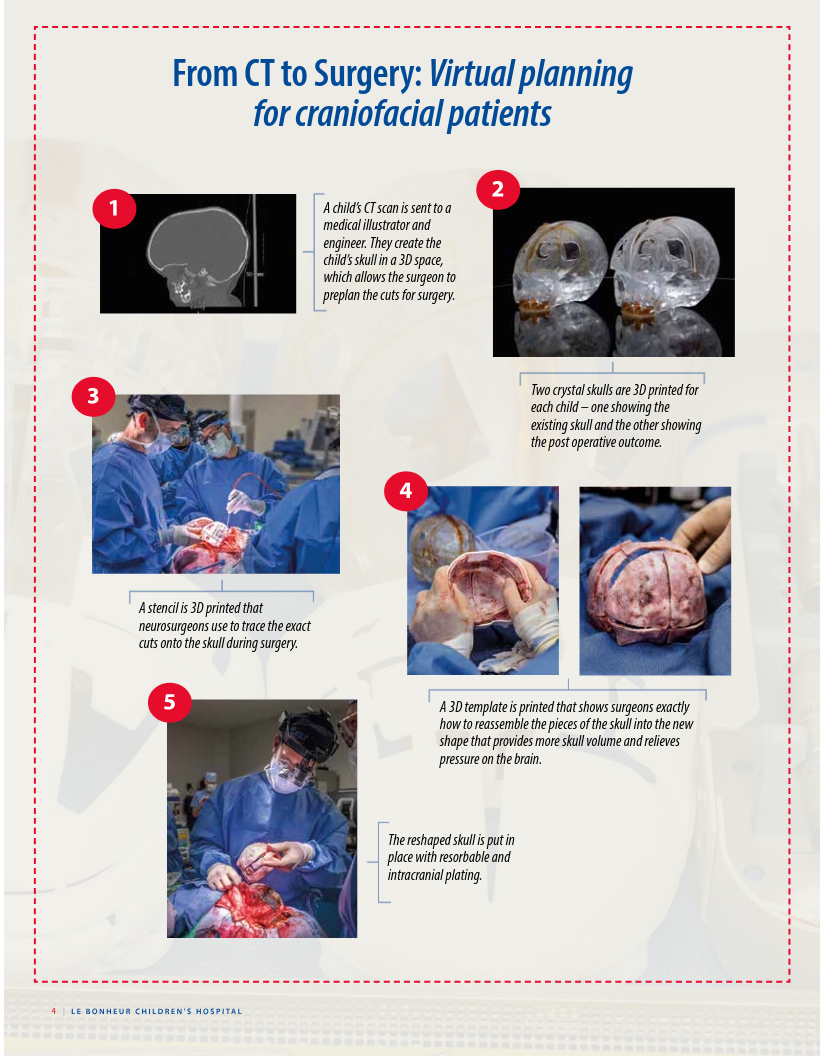

For children who need their skull reshaped and remodeled, such as those with craniosynostosis, Evans uses 3D virtual spaces and 3D printing as essential pieces to a successful surgery, from planning to the operating room.

To start the planning process, a child’s CT scan is sent to an engineer and medical illustrator who create 3D versions of the skull in a virtual environment. Working with these experts, Evans preplans the cuts in the skull that need to be made and decides how those pieces will fit back together for reshaping. This creates a second virtual skull showing the postoperative results. The two 3D skulls allow Evans to clearly measure the difference in skull volume before and after surgery, which relieves pressure on the brain that causes atypical development.

“Before the operation starts, I know what the result will look like and how much volume we can add,” said Evans. “There are many solutions but one that is probably the best option for each child. It’s much more like creating a piece of art.”

Once Evans finalizes his plan, the 3D printing work begins. Two crystal skulls are created for each child showing the skull as it currently is and how it will look post-surgery. These highlight the major structures of the skull and allow Evans an intraoperative reference point to make sure his approach is exact.

Next, a 3D stencil is created that outlines the places for cuts to create the exact skull pieces for reassembly. Neurosurgeons place this stencil directly onto the skull during surgery as a guide when cutting and removing the pieces of the skull.

Finally, a 3D template is printed that follows Evans’ plan for reshaping the skull. This template shows how each piece of skull fits together for the new skull shape. In the operating room, Evans uses the template to secure the pieces of the skull into the new shape with resorbable plates and screws.

Before the operation starts, I know what the result will look like and how much volume we can add. There are many solutions but one that is probably the best option for each child. It’s much more like creating a piece of art.

These techniques provide Evans and his team with precision planning down to the millimeter that mean better outcomes for kids and more options for surgical approaches. Evans says that the planning techniques and intracranial plating help kids recover quickly and often go home from the hospital one or two days after surgery.

“We are on the cutting edge and care a lot about accuracy in our reconstructions and obtaining measurable outcomes, including volumetric analysis and the millimeters we advance,” said Evans. “We want to know how to help kids better, be able to accurately measure our work and accurately reproduce it.”

Dynamic Measurements, New Solutions

Evans and the team not only use technology for the skull reshaping, but the soft tissue operations as well, such as cleft lip and palate repair or facial palsy surgery. Thanks to new 3D photography technology called 3dMD, Evans can measure the faces and heads of children in ways that were previously impossible and follow changes over time.

3dMD is a standardized 3D photography unit that uses visible light to capture 3D photos of the heads and faces of children with craniofacial conditions. The technology captures 3D shapes and color texture with photos taken 10 times per second. The data set produced with these photos can be viewed as a 3D color photo or video, smooth geometry model, wire mesh model or any combination of the three.

With this information, the 3D photography software then allows surgeons to determine distances, volumes and angles on a patient, as well as track dynamic information like the measurement of a child’s smile. When photos are taken throughout the course of a child’s treatment, the software also helps to determine changes in metrics such as the circumference or shape of the head after helmet therapy or craniosynostosis surgery.

“With 3D photography, I am able to be more precise and aware of small differences that would lead to a better outcome in the operating room,” said Evans. “We can measure exactly what’s wrong and apply it exactly in the OR. We also use a lot of analyses to follow these kids, and this is another way to monitor them and measure the size and shape of their skull to get very specific results.”

Evans believes the technology can move the field of craniofacial and plastic surgery forward. Thanks to a SPARK grant in collaboration with the University of Tennessee Health Science Center, he will partner with biomedical engineers, mathematicians and other surgeons to harness the power of the 3D photography through machine learning.

The group will train the model to analyze cleft lip and palate cases to develop unique surgical solutions that are smarter than what surgeons can develop on their own, says Evans.

A New Era

With a wealth of 3D technology, Evans and the Craniofacial and Cleft Program have a full toolbox to prepare precise plans for all types of craniofacial surgeries. These tools allow Evans to scientifically plan surgeries and measure outcomes while allowing space for the art of tailoring to the needs of each specific child.

“We have a big push in plastic surgery to quantify our outcomes and become better at what we do,” said Evans. “I think this is going to become a standard of care in this patient population.”

Help us provide the best care for kids.

Le Bonheur Children's Hospital depends on the generosity of friends like you to help us serve 250,000 children each year, regardless of their family’s ability to pay. Every gift helps us improve the lives of children.

Donate Now